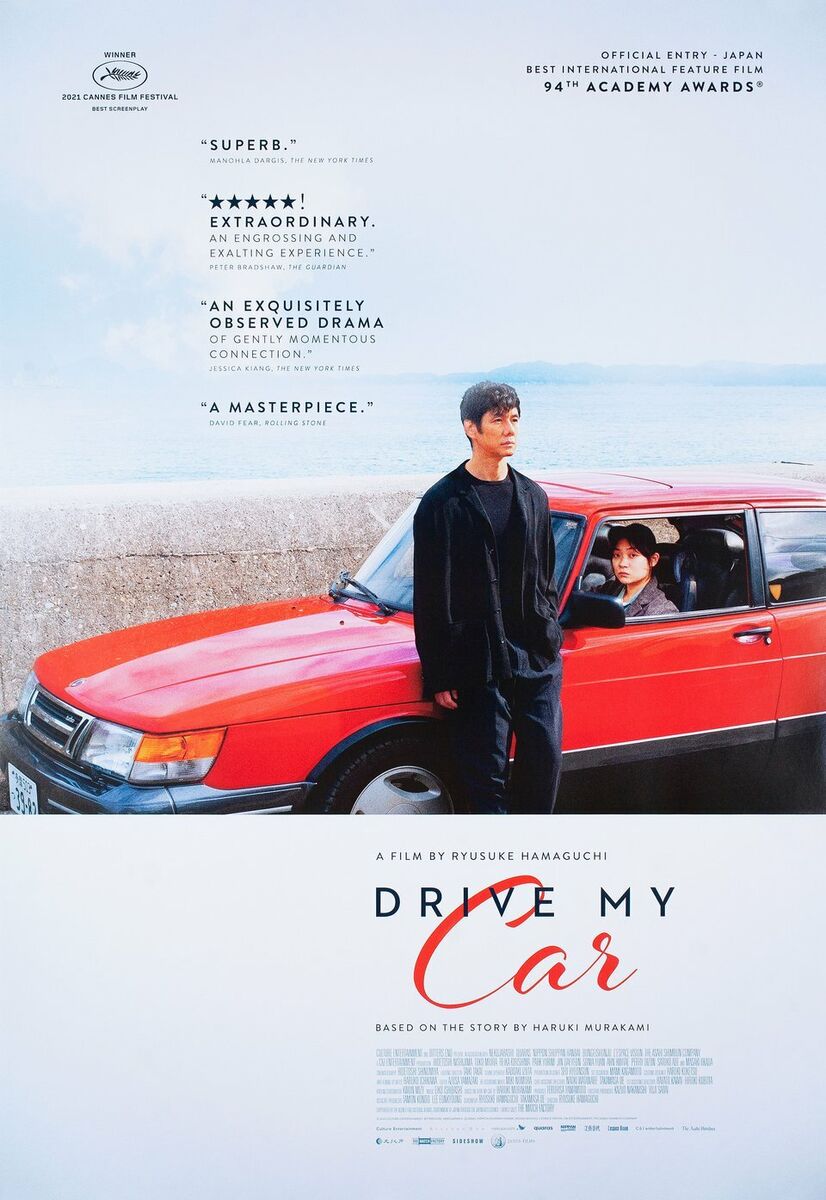

“Drive My Car” is a cinematic masterpiece that explores the grief and mourning that comes with losing someone so important in your life.

The film follows a middle-aged theater director and actor, Yusuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima), whose cheating wife, Oto (Reika Kirishima), suddenly dies from a cerebral hemorrhage the night she planned to confess to her infidelity, a fact Yusuke knew but had kept quiet about. Yusuke, though, instead blames himself for the death due to his late arrival home, dreading the inevitable conversation that would change the trajectory of their relationship. Two years later, Yusuke is in Hiroshima directing another production of Uncle Vanya, a production he typically stars in but instead opts out of due to the vulnerability that comes with playing the role of Vanya. Instead, he stars as the paramour of his late wife (Masaki Okada) in his typical role, a younger actor with several allegations of affairs with minor fans. One facet of his unique production of the Chekhov play is that every actor speaks in their native language, leading to issues with his actors who often retaliate. During his time in the city, he is forced to let another person drive his car for him, a 23-year-old woman named Misaki (Toko Miura), who is the same age as Yusuke’s daughter would have been if she had lived past four. Yusuke is forced to finally confront his grief after two years of mourning the most important person in his life.

One way that this film distinguishes itself as the academy award winner it is, is the way it creates a parallel between two of the major characters – Takatsuki, the younger lover of Oto, and Yusuke, the husband of the late Oto. Both heavily grieved the woman that passed, but to Yusuke, Takatsuki is all of the feelings and grief that he can’t release. What Takatsuki shows freely to a fault, Yusuke represses to a fault. At Oto’s funeral, Yusuke is found expressionless and downtrodden compared to the younger Takatsuki, who is openly in anguish. During Takatsuki’s audition for Uncle Vanya, he incorporates a huge influx of anger and attraction within the one or two minute audition he has with a woman whom he just met who speaks a different language. This scene is shown through a reflection in a mirror, the woman faceless due to Takatsuki’s blockage and Yusuke’s face next to Takatsuki due to the angling, showing a connection between the two. This event causes an outburst from Yusuke, who interrupts the scene after seeing too much of himself in the young man. I really enjoy the juxtaposition between the two, and it makes you wonder about Oto and how she had relations with men so entirely different. The mystery of Oto is one of the most enjoyable parts of the movie, one that is never truly explored, and I think that makes it all the better.

Throughout the film, the two build a relationship, one where Yusuke is forced to face himself for the first time since Oto’s death. Their relationship culminates into one moment where Misaki is driving the two to Takatsuki’s hotel after a dinner the pair had. In the car, Takatsuki reveals he knew things about Oto that Yusuke didn’t, the end of a story that Oto would reveal during relations with both lovers but apparently never finished with Yusuke. At the end of the story, Takatsuki declares in a beautiful monologue that he asks Yusuke to look within himself first before he ever tries to fully understand someone because he will never be able to fully understand.

I heavily enjoyed this scene and the relationship between the characters that formed out of a shared love of the same dead woman. When I watched the monologue scene, I couldn’t stop crying from the amount of emotion that Takatsuki puts into his words, a sort of sad smirk on his face and his eyes slightly teary. The way that the director makes the two so separate in grieving but all the same in mourning is just amazingly well done.

Another reason this film is considered a masterpiece is the strong connection between language and emotion. One major character in the movie is Yoon-A (Park Yu-rim), a mute Korean woman who speaks through KSL and is cast as Sonya, the niece of Vanya. Despite not speaking any words, Yoon-A is the most emotional part of the film. During her audition scene, without any particular reason, the tears just started to fall. I couldn’t place a reason, as the scene she was auditioning with was not emotional in its subject matter. Every scene with this young woman made my eyes start to water and my nose start to run.

Another instance of language and emotion is the tape recordings of Oto reading lines from Uncle Vanya that Yusuke listens to in the car religiously. It’s only when he becomes closer to Misaki that he is finally able to let go of the recordings of a ghost. The way she speaks, though, has no emotion in her voice – the way that Yusuke makes his actors act during line reads. It reflects the way Yusuke struggles with showing his true emotions and his tendency to ignore problems. I really enjoyed this aspect of the movie, and it shows the true human tendency to project onto others for the sake of ignoring what’s really wrong with oneself. I loved being able to watch the characters grow throughout the movie and watch Yusuke’s emotions finally explode at the end in Misaki’s hometown.

Overall, I would rate this movie, “Drive My Car”, a five out of five. The three-hour run time is filled with thoughtful and beautiful cinematography that showcases character growth and connections similar to real life. The human experience is shown in this movie about a man grieving his wife while directing a play, and I supremely enjoyed it.

Categories:

Looking at “Drive my Car” in the Rearview Mirror

0

More to Discover

About the Contributor

Movies are my life. Well, not completely, but I watch movies every other day during the school week. Every day on the weekends.

I’ll watch every genre, whether it’s science fiction or a romcom. No country is off limits for me either, as most of my favorite movies are not even in English. My favorite film that I have ever watched is Decision to Leave, a Korean film directed by the prestigious Park Chan-Wook. Right now, I’m planning to tackle every Park Chan-Wook movie in his filmography. Only 15 to go!

When I’m not watching movies or doing school work, I enjoy playing video games. I most recently finished playing Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, and I have my eyes on playing the original Final Fantasy VII, as well as Resident Evil 4. I like games that include a lot of story elements with a mix of fighting and puzzles. Recommendations are welcome!

I’m involved in a few clubs at school, including theater, A Novel Bunch, sophomore committee, tennis, and Project Lit. I plan to join Key Club next year, as I love to be involved in our school community and help with volunteering when possible.

I have four cats and a dog at home, and I love every single one of them. My favorite cat though, is Franky who I’ve raised since she was a kitten. Don’t tell my other animals!